Voicing Sexual Assault: installment 3

May 9, 2017

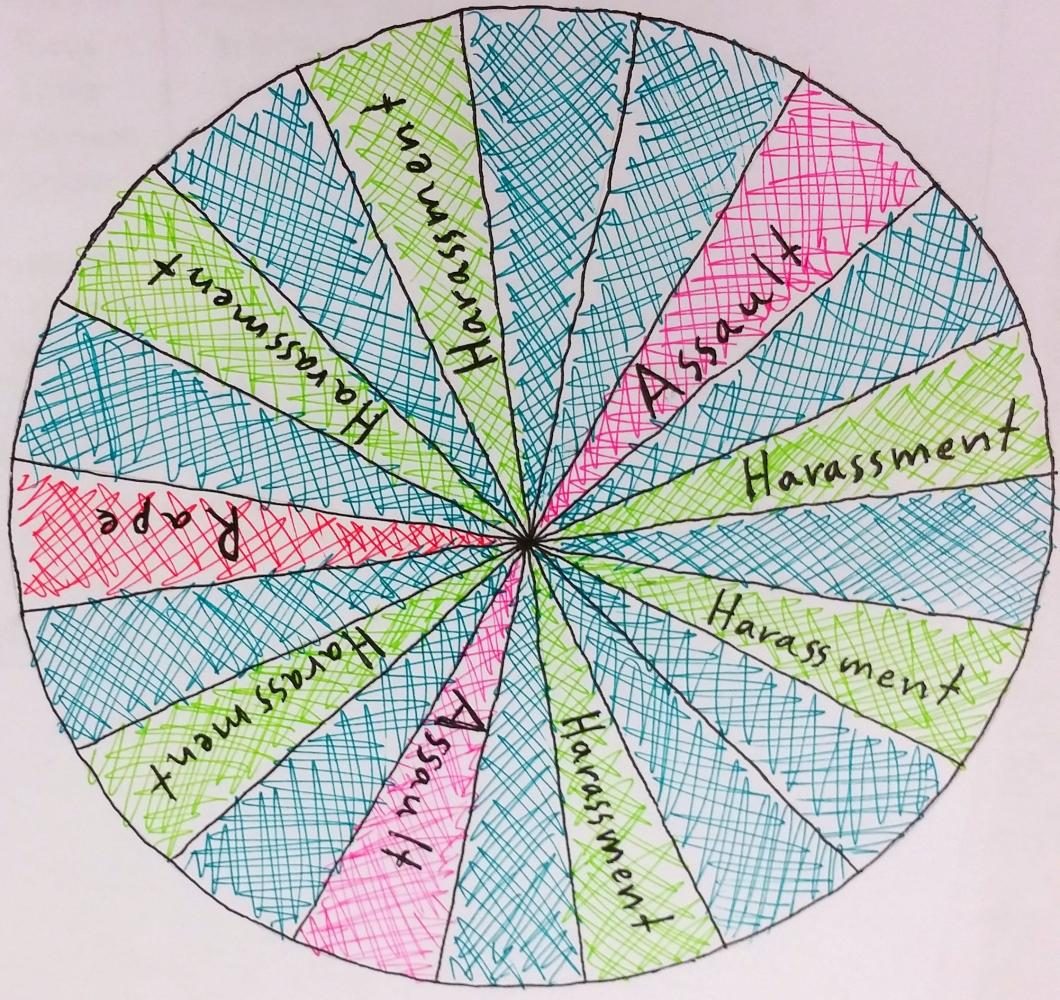

We’re back with another installment of the ongoing series covering sexual harassment and assault. To start off, we’re going to play a quick game of spin the wheel. There are twenty panels on our wheel. We’ll start off with rape and sexual assault, both attempted or completed, which take up three of our panels. Now on to sexual harassment. Add six panels for some type of verbal or physical workplace sexual harassment. That right there is a 9/20, or 45% chance of experiencing some type of sexual violence or harassment within your lifetime at a minimum.

Think about those numbers for a minute. Would you want to spin that wheel? Of course you wouldn’t. No sane individual would want to. But if you’re a woman, the choice isn’t yours. If you’re a woman, you had to spin that wheel of sexual violence the day you were born. It may not have happened yet, it may never happen, or it may have already happened but if you are one of the 162 million women living in America, the chances of experiencing one of the above types of sexual violence is obviously unacceptably high.

(See bottom of article for analytics on data for sexual violence and harassment statistics.)

Our latest interviewee shared their perspective on the issue of sexual harassment and assault within the walls of Harding. For purposes of anonymity, we will call her Jane Smith.

“Fear, uncomfortability, lack of education and awareness.” That’s how Smith characterized the overall issue of sexual harassment and assault.

She defined the act of sexual harassment as “any unwanted sexual remarks or unwanted, non-violent touching” and that it branches over into assault when the aggressor is “acting on sexual harassment in a violent manner.” She briefly summarized by saying “essentially, is there’s no consent, it’s harassment.”

She has experienced sexual harassment while at Harding, and that she “thinks sexual harassment is a problem” and that “the severity of the issue resides in the lack of awareness.”

“While I was bending over to get books from my locker, someone walked by and slapped my butt.”

While that scenario might not seem like much of a big deal, it does constitute sexual harassment and borders on statutory assault.

And it’s not just the aggressors who are in the dark about where to draw the line when it comes to harassment and assault: a 2015 survey of 2,235 full time female employees conducted by The Cosmopolitan showed that 16% of the respondents claimed to have not been sexually harassed, but responded “yes” to having experienced sexually explicit remarks, otherwise known as workplace sexual harassment.

‘This is where education on the issue would come in handy,” Smith said.

Smith reported that she is “often catcalled in public” and that “[sexual harassment] usually takes the form of unwanted comments about appearance and unwanted touching.”

“In the second case,” Smith said, “I used a rather rude four-letter word to tell them to go away.”

“I would not recommend my second course of action,” she said. “It only made the situation worse. The aggressor made comments about me being ‘feisty’ instead of backing off.”

“I don’t think they understood what was wrong,” Smith said. “[The] media glorifies unwanted attention and a lack of appreciation [for it] as ‘dedication’ or ‘playing hard to get.'”

“I think the main issue is a lack of education regarding what constitutes sexual harassment and assault,” she said. “The majority of harassment incidents could be solved if teachers were informed about what to look for.”

She also stated that she had not brought her case to the attention of the administration and that she “seriously doubt[s] that most people are willing to talk to the administration.”

“Administrators and police should take cases more seriously,” Smith said. “This may make victims more likely to talk to authorities.”

The effects of harassment and assault can reach far beyond the incidents themselves, as Smith elaborated. “Paranoia and fear are common responses in harassed women specifically,” Smith said. “I have observed family members who have altered their behaviors in order to combat harassment and assault. Not all of it is logical, but it is a product of fear.”

Even among other victims it is sometimes hard to find support. “The dialogue [between victims] is very limited,” Smith said. “It is mostly limited to ‘you should tell someone’ and ‘I don’t feel comfortable doing so.’ I think that goes back to the fear that occurs as a result of sexual harassment,” Smith said.

In an investigative radio piece titled “Once More with Feeling,” the NPR show This American Life broadcast a piece in which a “woman on the street” expository segment demonstrated that the cat-caller interviewed, named Zac, had a surprisingly nonchalant attitude towards the harassment he had been dishing out on a daily basis. Zac was under the impression that a) the women he harassed were not within their rights to request that he not harass them, b) that it was not harassment when confined to simple catcalling, and c) that the women he harassed were willing accomplices in the act, almost enjoying the harassment.

Eventually he came around to realizing the error of his ways, but as the reporter (Eleanor) states in the piece: “This was the most success I had with any of the guys I talked to. It took 120 minutes of conversation with one man to get him to commit to not literally assaulting women.”

Our source weighed in on this mindset and its potential effects at Harding. “This mindset lacks empathy and centers on narcissism. It would worsen the issue,” Smith said.

“[Victims] are the ones who feel violated” said Smith. “To make it stop they have to take the first step, despite the effort it takes and the uncomfortable-ness it causes.”

She offered some suggestions as to how one would go about combating sexual harassment. “Students can address the issue in two ways,” Smith said. “First, [aggressors] can be aware of their own actions and observe if they make those around them uncomfortable. Second, they can self-regulate by watching for sexual harassment and informing them that their behavior is not okay.”

“There is little that can be done to avoid sexual harassment,” Smith continued. “I would suggest avoiding situations with people or places where you know you are at an increased risk to be assaulted or harassed. If that is not possible, carry pepper spray and walk confidently.”

“I can’t limit other people’s words even if they are offensive,” Smith said. “Regarding actions though, in school I stand and behave confidently. I have also taken self-defense classes. Regarding words, I try not to encourage catcallers on the street.”

If you have a story to share or wish to be interviewed for a later installment (both anonymously), please to contact Mrs. Taylor in room 213, or contact either Nikita Lewchuk or Dylan DelCol.

If you have experienced sexual harassment or assault and are seeking support, contact your respective counselors.

For anonymous support, contact National Sexual Assault hotline at 1-800-656-4673.

*Statistics Analysis for Bureau of Justice’s Annual National Crime Victimization Survey (the data for the “spin the wheel” rape and assault numbers)

I’m sure at this point that some of you are questioning the numbers for our wheel

A quick google search will give you some numbers that, when examined, can be quite telling when it comes to the ongoing issue of sexual harassment, assault, and rape in the United States. To start of with the basics, the first of these is the US population. The United States has just under 319 million occupants. Next, take 50.8% of that to find the total number of women in the US. Google will waste no time telling you that those numbers equate to just over 162 million women.

Next, we examine the data collected by the Bureau of Justice as part of their annual National Crime Victimization Survey (NCVS). The statistics one can find in this pdf shows that the prevalence of rape and sexual assault among Americans as a whole (both genders) was 1.1 per 1000 people in 2014, with 284 thousand cases.

Now add to that the fact that the ratio of these cases between women and men is 9:1 respectively. To factor in those imbalances, we take the number of cases and find the percentage committed against women. This percentage is a shocking 90%. Ninety percent of 284 thousand is 255 thousand. That’s 255 thousand instances of sexual violence committed against women every single year.

Our final step will be to factor in the average life expectancy in America, which stands a bit over 78 years. If there are 255 thousand cases of sexual violence committed against women each year, then in the average 78-year lifespan of the average american woman, there will be nearly 20 million cases of sexual violence done against women. This staggering number can now be taken as a percentage of the female population of America, with 20 million cases out of the total 162 million women. 20 divided by 162 gives us the percentage of women who will experience sexual violence within their lifetimes. It comes out to 12.4% of all women in the United States. Just under one in every eight women. This gives us a number of 2.5 out of twenty. We averaged it with our second source survey.